A fresh water mass extinction: is it on the horizon?

In this blog I have spoken a lot about how

fresh water issues such as scarcity and contamination have affected humans, but

with the recent release of WWF’s Living Planet Report it seems like a

good time to discuss the effect these problems have on fauna and freshwater

ecosystems.

Despite covering less than

1% of the Earth’s surface, freshwater contains a disproportionate amount of

species, almost 6% in fact (at least 100,000), including around a third of all

vertebrates. However there is no doubt that they are under threat, largely, if

not entirely, down to human activity. Strayer

and Dudgeon, 2010 state habitat degradation, pollution, flow

regulation and water extraction, fisheries over exploitation and alien species

introduction as the primary causes of this, and there is an increasingly

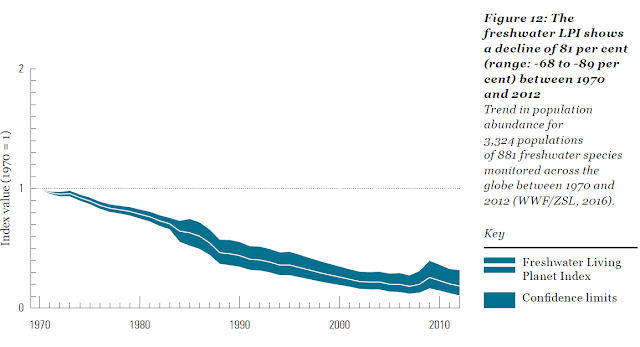

overwhelming case for adding climate change to this list. The Living Planet

Index revealed that global populations of vertebrate species had decreased by

58% between 1970 and 2012 with the decline being much more severe in the

freshwater ecosystem (81% - as shown in the following diagram) compared to terrestrial

(38%) and marine (36%).

The fact that 1970 is the starting point of

this study makes it likely that significant reductions in population of

freshwater species had already occurred. After the Second World War, the

building of dams proliferated peaking at around 5500 large dams being

constructed per year in the 1970s (Jones, 2014) and although the effects of

these are hard to predict, flow interruption can have negative effects on the

ecological integrity of flood plain rivers due to changes to patterns of

flooding and degradation of downstream channels (Ward and Stanford, 1995) as well as blocking

migratory species, and creating calm bodies of water with different

temperatures to rivers that may favour different species whilst encumbering

others. Dams also block sediment transport which can prevent vital nutrients

reaching floodplain soils (Holland, 2016). There were also fewer

regulations on industry back then which allowed the likely increased

contamination of waterways and in turn habitat degradation.

Since 1970, dam building has remained a

driver of this diminution as although construction has reached somewhat of a

standstill in Europe and USA, it is still prevalent in developing nations such

as China, Brazil and India and there is now 10,000km³ of freshwater stored in

dam reservoirs, a staggering five times the amount in surface rivers. The

reason for this vast amount of water being needed is of course the increasing

consumption of freshwater by humans that has occurred in line with population

increases (although these increases were also taking place pre-1970). The

following image shows dams being planned and in construction:

Another side effect of this population rise

is the over exploitation of fisheries that has taken place due to an

ever-increasing demand for food. This mainly refers to the unsustainable

harvest of fish from freshwater, but indirect over exploitation can occur as

other species are inadvertently caught in fisheries. Studies have concluded

that inland waterways and ecosystems have been poorly managed, and that fish

stocking has been prioritised over habitat management (Aps, Sharp, and Kutonova, 2004) which in the long term has resulted in declined

numbers.

In terms of how pollution

can affect fresh water ecosystems, it is similar to as mentioned in the

previous blog post on water contamination. Pollutants can include chemicals and pesticides, raw

sewage, petroleum and even thermal discharge. Toxic chemicals, such as PAHs

(polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons) and PCBs (polychlorinated biphenyl) released

from industry, and pesticides can have a range of life-threatening effects on

aquatic creatures. Depletion of oxygen levels can be triggered by nutrients

from agricultural runoff causing eutrophication, as well as the decomposition

of faecal matter (WWAP, 2006).

In 1970 when data collection for the LPI

started, climate change would not have been considered one of the primary

threats to global populations of wildlife. But as carbon dioxide emissions

continue to increase and global temperatures exceed 1°C above pre-industrial

levels, it can no longer be ignored. Fresh water ecosystems are especially

vulnerable to climate change because the species which inhabit them are largely

unable to move to a different environment as theirs changes. On top of this, fresh water temperature and abundance are both climate dependent – increased global

temperatures can lead to droughts and additional strain being placed on rivers

and wetlands with unsustainable extraction levels in order to irrigate crops. This

can result in these areas drying up with obvious loss of habitat.

So is there is a solution to this worrying

problem of population and species decline?

First of all, it makes sense to protect river

and lake ecosystems which are currently untouched. As for those regions which

have already been affected by human activity, reconciliation ecology is a term

that has been used to ‘encourage biodiversity in human-dominated ecosystems’.

It is a recognition that destruction of habitat takes its toll on species. Although

it generally applies to smaller, novel ecosystems, this concept is important in

changing mind sets towards preservation.

The LPI notes an increase in migratory fish

species since 2006, which it puts down to improving water quality in regions

such as Europe, and fish passes being added to man-made obstructions to allow

migrating fish to move through. If these could be applied globally, especially

in the previously mentioned nations where dam construction is still widespread

and water quality is generally lower, then it could have a huge effect.

Restoration of ecosystems to the condition they were in before humans interacted

with them is largely unrealistic, but dam removal projects are the closest

thing to this. A number of these have taken place in the USA, where outdated

structures are removed often leading to environmental restoration, although due

to the huge demand for freshwater from humans it is impossible to make dam

removal a widespread process.

There are definite steps forward but the

danger is that they are being overwhelmed by the setbacks which could lead to a

mass extinction of freshwater species.